FAQ 7: Guidelines for Use of Stainless Steel Underground

Stainless steel can provide excellent service underground. It is stronger than polymers and copper, and its resistance to chlorides and acidic soils is significantly better than carbon or galvanised steels.

Download ASSDA Technical FAQ 7 (PDF)

The performance of stainless steel buried in soil depends on the nature of the buried environment. If the soil has a high resistivity and is well drained, performance can be excellent even in conditions where other unprotected materials suffer degradation.

BASIC RULES

The Nickel Institute guidelines for burial of bare stainless steel in soil require:

- No stray currents (see below) or anaerobic bacteria.

- pH greater than 4.5.

- Resistivity greater than 2000 ohm.cm.

Additional recommendations include the absence of oxidising manganese or iron ions, avoidance of carbon-containing materials and ensuring a uniform, well-drained fill. If the guidelines are breached, then either a higher resistivity is required, i.e. measures to lower moisture or salts and ensure resistivity exceeds 10,000 ohm.cm, or else additional protective measures may be required.

In comparison, the piling specification (AS 2159) guidelines for mild steel require a pH greater than 5 and resistivity greater than 5000 ohm.cm for soils to be non-aggressive. It is rare for bare mild steel to be buried, i.e. typical specifications include a wrap or coating possibly with a cathodic protection system.

However, it is well established that even a carbon steel pile driven into undisturbed soil suffers only a few micrometers per year corrosion. This is because of the joint effects of lack of oxygen and the limited diffusion in compacted soil, which means corrosion products cannot escape and therefore stifle corrosion reactions.

SPECIFIC ISSUES

- Uniform soil packing is required as variable compaction can induce differential aeration effects.

- Avoid organic materials in the fill around buried stainless steel as they can encourage microbial attack.

- Avoid carbon-containing ash in contact with metals in soils. Localised galvanic attack of the metal can occur.

- Oxygen access is critical. Having good drainage and sand backfill provides this. A sand-filled trench dug through clay may become a drain and it is not appropriate. Stainless steels generally retain their passive film provided there is a least a few ppb of oxygen, i.e. 1000 times less than the concentration in water exposed to air.

- Chlorides are the most frequent cause of problems with stainless steels. In soils, the level of chlorides vary with location, depth and, in areas with rising salinity, with time. High surface chlorides may also occur with evaporation. This is a problem for all metals although stainless steels are not usually subject to structural failure.

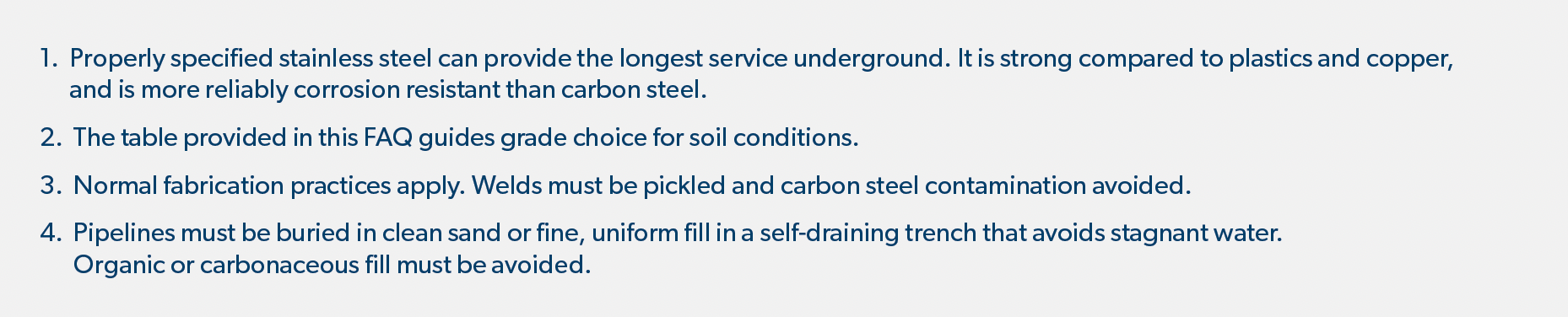

The general guidelines for immersed service that are in neutral environments at ambient temperatures and without crevices, 304/304L may be used in chloride levels of 200 ppm, 316/316L up to about 1000 ppm chloride and duplex (2205) up to 3600 ppm chloride. The super duplex alloys (PRE>40) and the 6% molybdenum super austenitic stainless steels are resistant to seawater levels of chloride, i.e. approximately 20,000 ppm. These guidelines are easy to apply in aqueous solutions.

Soil tests for chlorides may not exactly match actual exposure conditions in the soil. Actual conditions may be more (or less) severe than shown by the tests. The difference is calculable but in practice, the aqueous limits can be used as general guidelines. More specific recommendations, based on published guidelines, are provided in the table above.

It may seem redundant to asses both chlorides and resistivity. Both are required as the resistivity is primarily affected by water content and if it is low, then quite high chlorides could be tolerated. Despite these recommendations, most Australian practice is to use 316/316L or equivalent, primarily because of variable soils.

- Good drainage and uniform, clean backfill are essential for bare stainless.

- Duplex or super duplex could be replaced with appropriate austenitic and 304/304L could be replaced with a lean duplex.

- Ferritic stainless steels of similar corrosion resistance (usually classified by Pitting Resistance Equivalent [PRE]) could also be used underground.

Potential acid sulphate soils are widespread, particularly in coastal marine areas as described in https://www.qld.gov.au/environment/land/management/soil/acid-sulfate/identified. Once disturbed and drained, which also allows oxygen access, such soils typically become more acidic than pH 4 and will attack metals (although stainless steels will be less readily attacked than other metals). Detailed assessment is required if using metals in such an environment as the effect of other aggressive ions is likely to be more severe at low pH.

CASE STUDIES

- Nickel Institute Publication No. 12005 describes a five-year burial exposure in Japan at 25 sites with highly varied corrosivity. After five years in marine sites, horizontal 304 pipes showed no pitting but some crevice attack under vinyl wrap. Only one 316 pipe showed any attack. Vertical 304 pipe suffered attack near the base at some sites apparently due to differential aeration effects. There was also some manganese staining.

- An Idaho study of a 33-year NIST burial found 12% Cr martensitic perforated. The 'lake sand' site had high ground water with pH 4.7 at recovery. Sensitised 304 was attacked worse than annealed but both suffered attack along the rolling direction from edges. 316 was not attacked even if sensitised. Assessment included radiography to ensure the sub-surface pitting and tunnelling was detected despite negligible mass loss.

- A seven-year European study with approximately 800 samples included austenitic and duplex alloys in three marine and five other environments buried either 1.5 m or 0.5 m underground. Creviced samples often corroded in marine environments. Overall alloy type was not relevant for corrosion but chloride content and aeration were critical and, unusually for underground, there was some effect from temperature. Resistivity was seen as a proxy for chloride and moisture. No obvious trend was seen from pH, sulphide, sulphate or calcium carbonate levels. Metal potential was not an indicator of corrosion. Full details of the program have been published at EUR 23586.

As noted above, duplex stainless steel of similar corrosion resistance (PRE) to 304 and 316, respectively, are expected to provide similar results when buried.

On a more practical level, there are several common approaches that are used when burying stainless steel:

- Wrap the stainless steel pipe in a protective material, such as a petrolatum tape, prior to burial. If the wrapping is effective (typically an overlap of no less than 55% of the wrap width is specified), then the nature of the external surface of the buried pipe is of no consequence. In this case, stainless steel is only used for its internal corrosion resistance, i.e. its resistance to corrosion by the fluid which the pipe is carrying. Some authorities prohibit this practice because of concerns that damage to the wrap could cause a perforating pit in severe environments.

- Ensure that the soil environment surrounding the buried stainless steel is suitable for this application. In this case, the trench is dug so that it is self-draining, without there being areas where stagnant water can accumulate in contact with the buried pipe. The stainless steel pipe is then placed on a sand or crushed aggregate bed and covered by similar material. Under these circumstances, 316 grade stainless steel can be quite a suitable choice. US practice is to use 304, but Australian soils are quite variable and there have been mixed experiences with 304.

- Above ground sections of pipework are often stainless steel as they are at risk of mechanical damage while underground pipework is polymeric - polyethylene (PE) or fibre reinforced plastic (FRP) - despite the risk of damage due to soil movement.

In all these cases, the assumption is that the stainless steel has been fabricated to best practice. This includes pickling of welds (or mechanical removal of heat tint and chromium depleted layer followed by passivation to dissolve sulphides) and ensuring contamination by carbon steel has been prevented. It is also assumed that the buried stainless steel does not have stickers or heavy markings that could cause crevices and lead to attack.

STRAY CURRENTS

All buried metals, including stainless steels, are at risk if there are stray currents from electrically-driven transport, incorrectly installed or operated cathodic protection systems, or earthing faults in switchboards. Stray current corrosion can be identified as it causes localised general loss rather than pitting. It is also very rapid.

WHAT TEST METHODS ARE USED?

There are Australian and ASTM standards giving basic measurements of resistivity on site with 4 pin Wenner probes or in a soil box in a laboratory. More detailed checking includes water content, chlorides, organic carbon or Biological Oxygen Demand (BOD), pH or redox (or Oxidation Reduction Potential [ORP]) potential - which assess microbial attack risk but also captures the effect of oxidising ions and dissolved oxygen. Most of these test methods are covered in 'Soil Chemical Methods: Australasia' written by George E. Rayment and David J. Lyons and published by CSIRO.